Biography

Hoagland Howard Carmichael was born in 1899 in Bloomington. His father was an itinerant laborer who moved his family throughout the Midwest looking for steady work, always returning to Indiana. “Home” was back in Bloomington, where they’d left his wife Lida’s golden oak piano. She helped support the family by playing at the local movie house and for university dances. “Ragtime was my lullaby, ” Hoagy said, and though his mother was thrilled when he picked out a tune on the golden oak, she warned him: “Music is fun, Hoagland, but it don’t buy you cornpone.

Lida Carmichael thought her ...

Hoagland Howard Carmichael was born in 1899 in Bloomington. His father was an itinerant laborer who moved his family throughout the Midwest looking for steady work, always returning to Indiana. “Home” was back in Bloomington, where they’d left his wife Lida’s golden oak piano. She helped support the family by playing at the local movie house and for university dances. “Ragtime was my lullaby,” Hoagy said, and though his mother was thrilled when he picked out a tune on the golden oak, she warned him: “Music is fun, Hoagland, but it don’t buy you cornpone.

Lida Carmichael thought her son might grow up to be president of a railroad. He might have, too, because ambition burned hot in him, but in 1919 he heard Louie Jordan’s band (not to be confused with Louis Jordan who had a popular band in the thirties) in Indianapolis and this black ensemble of early jazz players “exploded in me almost more music than I could consume.”

Hoagy went on to study law at Indiana University but he was already a “jazz maniac” and his own band, The Carmichael Syringe Orchestra, was made up of a gang of loose cannons whose spiritual leader was a Dada-inspired poet named Monk. “There are other things in this world besides hot music,” Monk advised Hoagy in a serious moment, “I forget what they are–but they’re around.” Those ‘other things’ were named Dorothy Kelly, and to Hoagy she was more than first love. Dorothy was a secure respectable life in one of those big houses up on the hill in Bloomington he’d dreamt of as a boy, and when he held her in his arms, that was what he wanted more than anything else.

Then Hoagy heard a young white cornetist named Bix Beiderbecke and, “it threw my judgment out of kilter.” This was a sound like nothing he’d heard before and when Hoagy played an improvised tune for Bix, the strange young man with a magical horn said, “Whyn’t you write music, Hoagy?” The rest of his life was the answer to Bix’s question.

Many years later, when an audience saw the mature Hoagy sitting at the piano singing “Lazybones” or “Ole Buttermilk Sky” in what he called his ‘native wood-note and flatsy- through-the-nose voice,’ it looked so natural and relaxed that it was easy to assume he’d led a charmed life. But Hoagy’s road to success was just as bumpy and lurching as his friend Bix’s was smooth and quick.After a modest but deceptive early success with “Washboard Blues” and “Riverboat Shuffle,” Hoagy packed a bag and went to New York. But he soon found himself scuffling around the cold, lonely town, not selling anything but bonds in a bottom-end job at a Wall St. brokerage house. “I’m singing the music publisher’s theme song-it ain’t a commercial,” he wrote back to Monk. He tried to give up–more than once–but the words of another old friend kept him going. Reggie Duval, a black barber and dance hall pianist in Indianapolis, was the only teacher Hoagy ever had besides his mother. Reggie had taught Hoagy how to make music ‘jump’ and also gave him a creed to live by: “Never play anything that don’t sound right. You might not make any money–but at least you won’t get hostile with yourself.”

Hoagy kept writing what sounded ‘right’ and in 1930 made recordings of “Georgia On My Mind,” “Rockin’ Chair,” and “Lazy River.” Other artists heard the new songs and within a year Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and the Dorsey brothers had recorded their own versions and were performing them on the new hot medium, radio. Hoagy Carmichael himself was still barely known to the public, but they were hearing and singing his songs, and in 1936 Hoagy went to Hollywood where “the rainbow hits the ground for composers.”

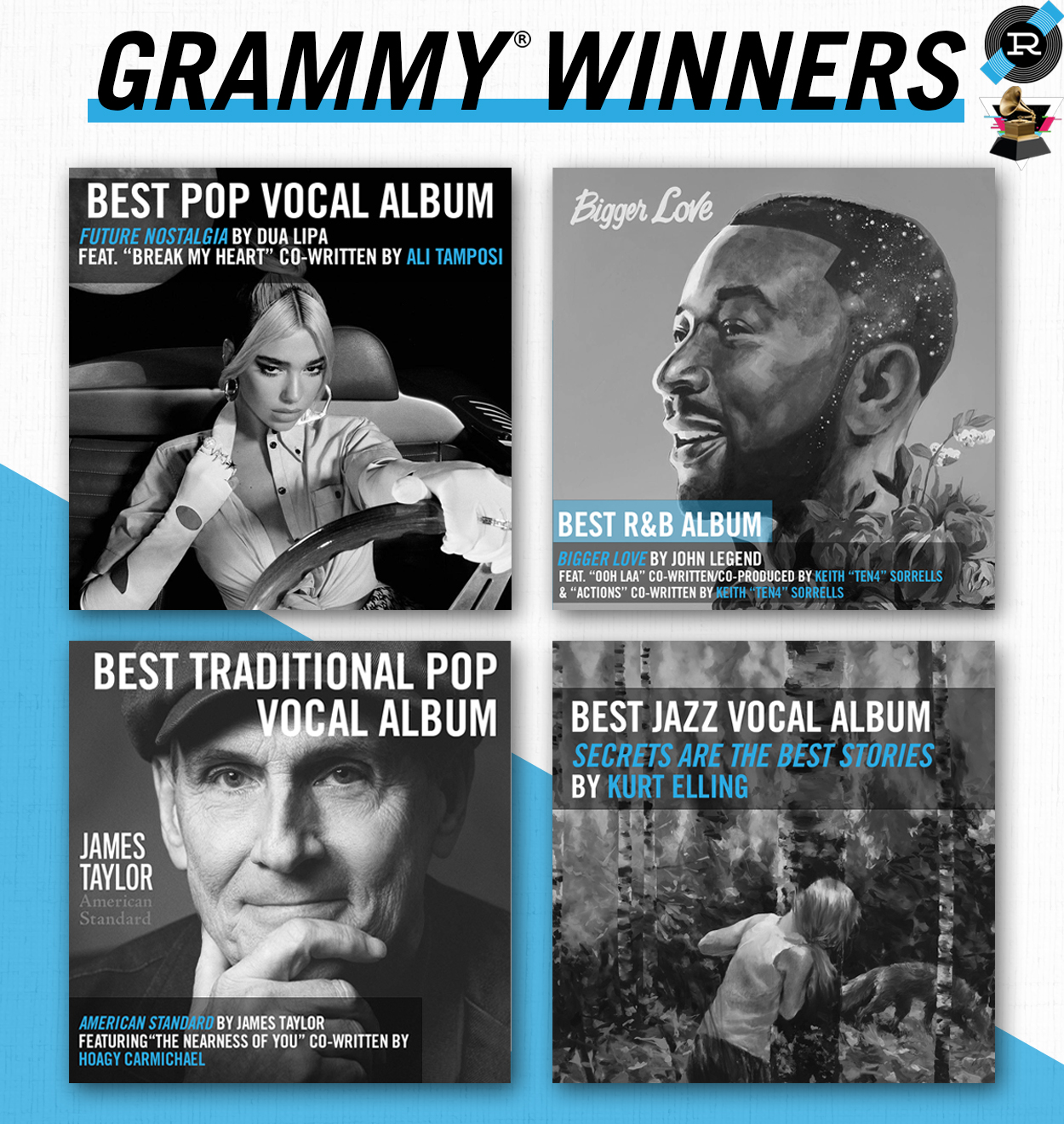

During the next decade, Hoagy moved from backstage into the spotlight. He worked with lyricists Johnny Mercer, Frank Loesser and Mitchell Parish. He became a star performer on records, radio and stage with a signature style, and began appearing in movies, most memorably in “To Have and Have Not” and “The Best Years of Our Lives”. He got married and fathered two sons. In one year, 1946, he had three of the top four songs on the Hit Parade, and in 1951 he and Mercer won an Oscar for “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening.” He hosted his own television show, “The Saturday Night Review.”

‘Hoagy’ was no longer a peculiar name, he was a star, even an American icon. He was also someone you knew, a guy you wished you could have a drink and share a laugh with. He had the same joys and desires, disappointments and fears you had, and some of his songs–“Lazy River,” “Heart and Soul”– became so familiar they sounded as if no one had written them, they’d just always been there.

Despite Hoagy’s folksiness, humor and accessibility, there was also something emotionally deep and complex in him. Perhaps it was because he never got that house back in Bloomington, even if he got one in Hollywood instead. Or maybe it was because behind that knowing look and wryly cocked eyebrow there were a whole lot of things that baffled him too. Like how you could want more than anything “the solid, warm, endearing things of life” and also be a “jazz maniac” whose judgment was “thrown out of kilter” by hearing a horn. These were the twin passions which wove through Hoagy’s life in strands, and one night when he was alone at the piano, they combined in a song.

Hoagy described his surprise the first time he heard a recording of “Stardust”: “And then it happened–that queer sensation that this melody was bigger than me. Maybe I hadn’t written it at all. The recollection of how, when and where it all happened became vague as the lingering strains hung in the rafters of the studio. I wanted to shout back at it, ‘maybe I didn’t write you, but I found you.'”

Hoagy found a lot of songs during his storybook life, and maybe his personal journey began the night a hungry young kid heard Louis Jordan’s band and went crazy for jazz. In The Stardust Road, Hoagy describes what he said to himself the next day mowing his Grandmother’s lawn: “No, gramma, I don’t think I’ll ever be president of anything. I know Mother named me after a railroad man, but it’s too late now, I’m afraid. Much, much too late.